Orthorexia: Just another buzz word? An eating disorder?

The last 2 years have shown a visible increase in literature on the topic of orthorexia nervosa, despite not actually being in the DSM-5. Does this lack of “true” diagnosis make this condition just another buzz word, or is this the start of a new breed of eating disorders? Furthermore, is the lack of diagnostic criteria ignoring a whole new subset of those with disordered eating under the guise of “health”?

Definitions and Diagnostic Criteria

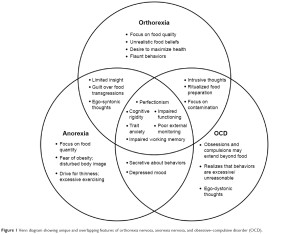

Orthorexia literally means “proper appetite”, a misleading name given the ramifications of those cited with orthorexia. It was first described in 1997 by Bratman and Knight after Bratman described his own experiences with orthorexia. The symptoms vary from focusing purely on “clean” or “healthy” food to feelings of deep guilt when going “off plan” or eating something “not clean.” Compensatory behaviors that are often found with those who suffer from anorexia nervosa or bulimia are very similar. Orthorexics will exercise compulsively to “make up” for their “mistakes.” They also obsess over nutrition labels and will start to isolate themselves from social events surrounding food for fear of going off their diet. These criteria all shadow behaviors of other eating disorders as well as obsessive compulsive behavior.

From “The clinical basis of orthorexia”, a venn diagram showing the overlapping criteria of orthorexia, anorexia and OCD

Orthorexia’s onset can be more insidious than this extreme behavior, though. Often someone starts off wanting to “eat healthier.” They decide to remove a food group from their diet, then another, then another. Before too long they have a very strict set of rules around what they can and cannot eat. These rules and structure make them feel safe and in control, and as long as they abide by them they are eating “healthy”.

One very, very important distinction is that this group has no medical, religious or ethical reason to avoid certain food groups. While those suffering from orthorexia will often claim they are allergic or intolerant to dairy, gluten, etc. they often have never been formally diagnosed. Most of those who suffer from orthorexia have self-diagnosed allergies and intolerances to food groups. Those who do actually suffer from allergies and are intolerant to certain food groups may still fall into other categories of disordered eating, however for the sake of this discussion we will not include them.

One major departure from orthorexia and anorexia (according to research) is the motivation behind the disorder, though I personally disagree. Anorexia’s end motivation may be about weight loss, but there is never “skinny enough” for those with anorexia. They often are unable to see how sick they truly are. I would argue that anorexia is ultimately about control, and here it doesn’t depart too sharply from orthorexia. The suggested criteria for orthorexia points to a need for those to feel “pure” or “clean” by controlling what goes into their body. This mirrors the controlling aspect of anorexia. However, those with orthorexia are quick to flaunt their behaviors, while anorexics are very secretive about theirs. More on this can be read in the paper included at the end of this article.

The Dark Consequences of Orthorexia

Some might argue that orthorexia is a word used by those who “don’t get it” to describe the passionate. Without an official diagnostic criteria this might be true, however it’s impossible to ignore the consequences of unchecked orthorexia. Unchecked orthorexia can mirror a lot of the consequences of anorexia. For example, omitting entire food groups can lead to deficiencies in certain micro and macronutrient groups. Side effects include anemia, osteopenia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, and others.

Other consequences involve the effect it can have on your social life. Food anxiety makes any social outing involving food almost impossible for those with orthorexia. Given the serious overlap between orthorexia and anorexia they’re prone to the same binge-restrict cycles as those with anorexia. Deviations from their diet are met with self loathing and guilt. They spend an inordinate amount of time researching, planning and excluding foods from their diet.

Causes

Since this condition is not officially diagnosed, nor is there outstanding data involving its manifestations and treatment, it’s hard to pin point the specific causes of orthorexia. However, there are some places we can look to understand the obsession around health and purity.

- Fake trainers or nutritionists: Every celebrity is endorsing some diet these days with very little understanding of the consequences of their support. It’s not hard to find a book, website, or blog touting a certain type of diet or food exclusion as THE way to lose weight or become healthy. In fact, there are entire companies built on the insecurity of the average person, creating groups and “coaches” out of everyday, unqualified people. While some of these people may mean well, they ultimately are unqualified to give advice about diets. This creates and endless cycle of misinformation, usually involving statements like “I saw celebrity name gave up gluten, so I did, and now I feel amazing!” or “I recently started pyramid scheme diet here, and I lost 20 lbs!” While these statements may be innocent in the beginning, they can quickly lead to feelings of guilt when strayed from. Since they focus on excluding food groups they may eventually lead to the same social anxiety described by many with orthorexia.

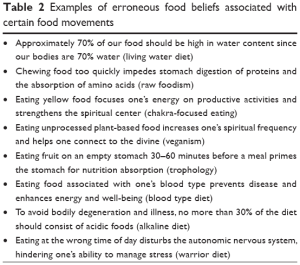

Examples of misinformation found in popular diets, all which have been discredited but are still touted by popular diets. Source: The clinical basis of orthorexia.

- Weight loss/health as a social status: We are often to praise people for losing weight or being healthy without truly understanding what it meant to that individual. “Healthy” and “fit” are a social status that are openly praised. Someone who updates social media with their workout or posts about not indulging in the bagels at work are seen as “strong” and someone to look up to. Diets are often associated with strength and willpower to the point where those who don’t adhere to diets 100% are seen as “weak” and “lack willpower.”

- Good Food/Bad Food Dichotomy: The minute certain food groups are seen as “bad” or “unhealthy” a dichotomy is created. Labeling food as “good” or “bad” without any true understanding of what it means to an individuals diet or health is unrealistic and unhealthy. Research has shown time and time again that if you tell someone they can’t have a certain food type they will crave it. This can contribute to the food binges experienced by orthorexics when they eat one thing off their “meal plan.”

- Fad Diets: Researchers have noted that orthorexia patterns of food aversion parallel whichever fad diet is currently circulating.

Where To Go From Here

I have stated many times that this condition lacks an official diagnostic criteria, and is not currently recognized by the DSM-5. However, the National Association for Eating Disorders has been compiling data on the topic and has a page devoted to education on orthorexia. This topic has also been explored by a number of popular websites around health and fitness. While it is not currently an eating disorder it IS a type of disordered eating. It is something that interferes with daily life and disallows enjoyment of life. If you feel that you’ve spent an inordinate amount of time worrying about food, or you feel like you might have orthorexia, it is important to seek the health of a trained professional. Disordered eating can lead to eating disorders, and the associated complications from dietary restrictions are severe enough to warrant intervention in some cases.

If you’d like to learn more about the current research of orthorexia, The clinical basis of orthorexia: emerging perspectives is a great paper to help inform you about orthorexia.